At Tamil Nadu unit behind Madhya Pradesh cough syrup deaths, telltale signs of negligence

The gate of Sresan Pharmaceutical Manufacturer stands shut, two khaki-clad policemen bent over notices pasted on a blue wall. Above them, a faded signboard carries the name of a firm now at the centre of a fatal drug scandal. Inside, the rooms are bare but reek of hurried abandonment: Stacked plastic jars, stained concrete floors, hoses still snaking across the ground. Windows are closed tight, some blocked with makeshift barriers. The air is stale, as if the workers had left mid-shift.

Through a narrow window, the facility reveals itself as stark and unhygienic. Piles of white and blue plastic containers lean against the wall, some still stained with residue. On the floor sit black buckets, metal frames, and the scattered lids of giant drums. In the backyard, among ash and debris, half-burnt labels of Pronic Iron Syrup and discarded 200ml bottles of Cyproheptadine hydrochloride syrup IP lay in the open. Also, labels showing “Sresan” in red script, curled at the edges, the printing charred by fire.

Story continues below this ad

Also unmissable are the blue barrels, their label declaring the contents: Liquid Glucose, 300.80 kg net weight — “not for retail sale,” manufactured in June 2025, with an expiry date of June 2027.

Saravanan, who lives nearby, said he often saw women in green uniforms walking in around 9.30 am and leaving at 5 pm. “There were about ten of them,” he recalled. “They told me the facility would shut by December, since their license was expiring.” According to shop owners and neighbours, it has been functioning for the past 13 years or so. They knew some syrup was being manufactured there, but none of them had an opportunity to enter the facility. “The workers all came by bus – no one from this neighbourhood,” said Venkitesh, who works at a nearby automobile showroom.

An FIR was lodged against Dr Praveen Soni.

An FIR was lodged against Dr Praveen Soni.

On Tuesday, the Tamil Nadu Drugs Control Department pasted two separate show-cause notices on the wall outside, addressing the proprietor, Dr G Ranganathan, and K Maheswari, the firm’s analytical chemist. The documents, running several pages, accuse the company of grave violations under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940.

One notice declared that “the sample has been declared as Not of Standard Quality by the Government Analyst (Drugs), Drugs Testing Laboratory… The sample is found to be adulterated, since it contains Diethylene Glycol (48.6% w/v), which is a poisonous substance which may render the contents injurious to health.”

Story continues below this ad

The notice ordered the firm to explain why action should not be taken against it. The firm was also told to recall all stock, submit complete distribution records, and furnish documents ranging from master formula records to purchase invoices for raw materials such as propylene glycol.

Another charge was “misbranding”: the syrup labels failed to carry a mandatory warning – “Fixed dose combination shall not be used in children below four years of age” – as notified by the Union Health Ministry in April 2025.

Both Ranganathan and Maheswari were given five days to respond. Both were unavailable for comment.

After the deaths of children in Madhya Pradesh, the chain of accountability that led to this quiet industrial cluster near Sriperumbudur began hundreds of miles away. From Bhopal, Dinesh Kumar Maurya, Controller of Food and Drug Administration, Madhya Pradesh, wrote a letter to his Tamil Nadu counterpart: “As you are aware, death of children (has been) reported in the District of Chhindwara… As the manufacturer is located under your area of jurisdiction, it is requested to take necessary action in the matter and provide details of the above-mentioned drug supplied and action taken.”

Story continues below this ad

The letter prompted Tamil Nadu’s Drugs Control to act, with the CDSCO Indore sub-zone coordinating. In Chennai, the case has triggered a state-wide alert. Chemists have been instructed to pull suspect stocks, hospitals have been warned, and distributors are being scrutinised.

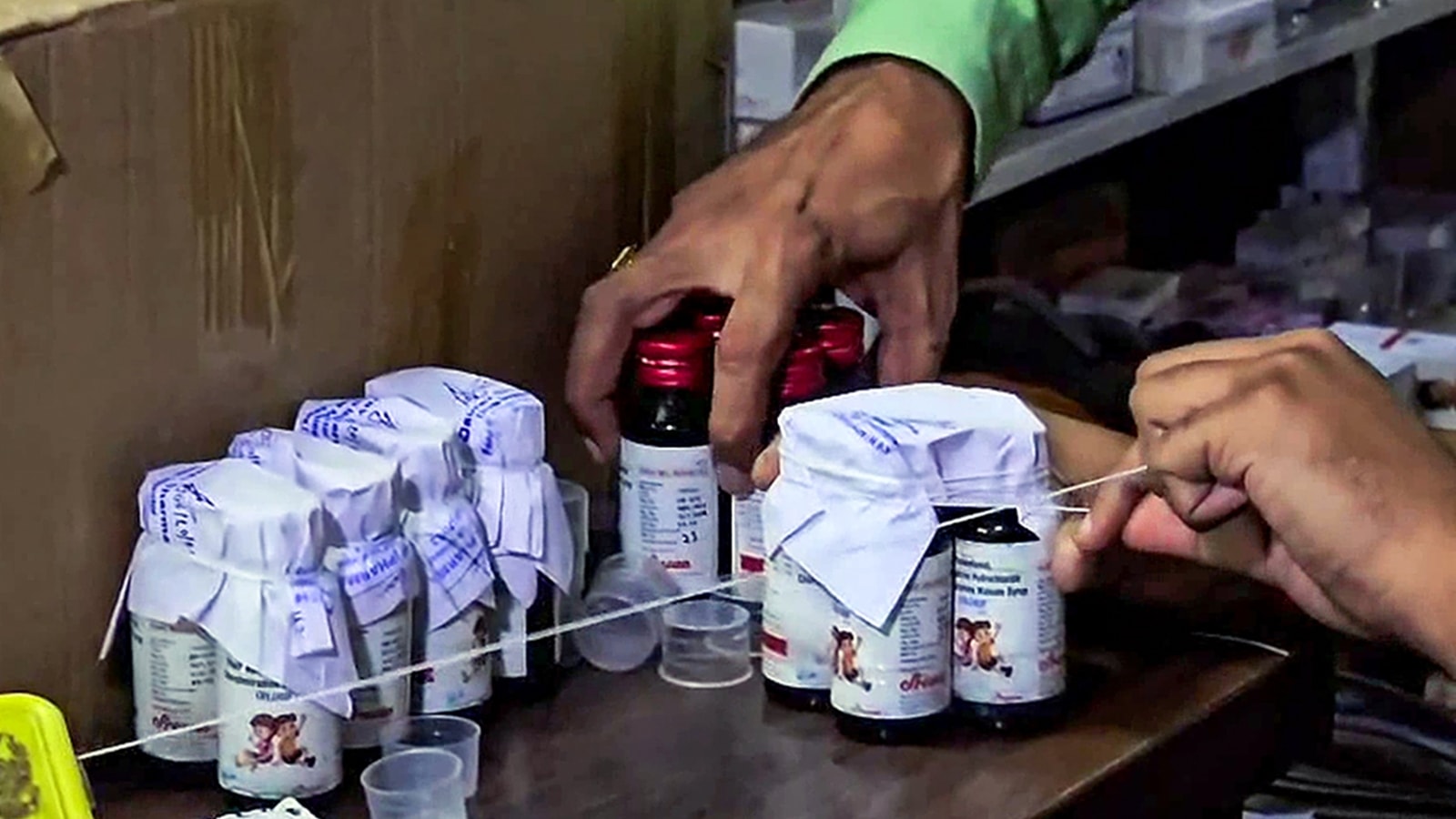

Officials seal Coldrif cough syrup bottles in Chhindwara, MP, on Sunday. (ANI)

Officials seal Coldrif cough syrup bottles in Chhindwara, MP, on Sunday. (ANI)

The unit, its history

The Indian news has found that when the team of inspectors from Tamil Nadu’s Drugs Control Department knocked on the doors of building number 787, which the unit ran out of, they found a list of 364 violations.

Ranganathan, whom the Special Investigation Team (SIT) of the Madhya Pradesh police is looking for, procured a manufacturing licence on October 27, 2011. It was valid until 2026.

But this was not his first foray into pharmaceuticals.

Story continues below this ad

An analysis of the Registrar of Companies (ROC) documents reveals that Ranganathan was the director of the now-defunct Sresan Pharmaceutical Limited, which was incorporated on December 25, 1990. As per records from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA), the company status was designated as struck off in 2009, implying it shut down operations sometime that year.

According to the ROC documents, the firm’s turnover and total expenditure were both zero that year. Chhindwara Superintendent of Police Ajay Pandey said, “When we tried to find out about the directors (of Sresan Pharmaceutical Manufacturer), we saw they were also part of a company that has been defunct since 2009. We will know more once we question them.”

The same syrup has been linked to the death of 14 children in Madhya Pradesh’s Chhindwara district.

The same syrup has been linked to the death of 14 children in Madhya Pradesh’s Chhindwara district.

Tamil Nadu Assistant Director of Drugs Control Deepa Joseph, whose team inspected the premises, said, “We questioned Ranganathan, who told us that his earlier company shut down in 2009. He then opened a sole proprietorship the same year under the name Sresan Pharmaceutical Manufacturer and obtained a license to sell the products. As of now, he and the staff are not available at the premises.”

As per the company’s GST filings, its core business activity was listed as manufacturing promethazine, chlorpheniramine, astemizole and cetirizine, which are used to treat allergies, cold symptoms, runny nose, etc. It also deals in preparations that help improve haemoglobin levels.

Story continues below this ad

In its investigation report, the drug control authorities laid bare how this unit functioned with a skeletal staff with insufficient training and infrastructure.

During the visit on October 1 and 2, the drug control inspectors stated that the wall, floor and ceiling of core areas had cracks, the unit did not have air filtration facilities to prevent contamination, its doors were made of aluminium with no interlocking facility, and the products were all mixed “in one room using plastic pipes” and other “cracked and leaking equipment”. A domestic gas cylinder was used for “dissolving a few raw materials”.

There was no system in place to “review and investigate product complaints” or a procedure to recall products. Joseph said it was a “small manufacturing company with very limited distribution”. The company was once red-flagged after quality issues cropped up in its hand sanitisers during the Covid pandemic.

“The company has fewer than ten staff members,” Joseph said.

Story continues below this ad

As per the officer, such a unit requires one manufacturing chemist and one testing chemist, along with some supervisors, to qualify for the licence.

According to the Tamil Nadu Drugs Control Department, there were over “350 minor and major violations”. The violations range from using raw materials not of pharmacopoeial grade, leading to low-quality products, to not documenting the process of manufacturing.

“It is the company’s responsibility to maintain proper records online. They did not maintain purchase records for raw materials like propylene glycol, which must be bought only from licensed professionals. The raw materials were not of pharmacopoeial grade, and the products were found to be not of standard quality,” Joseph said.